On the joys of not renovating a house in France.

By Megan Harlan

In the previous piece I considered the dream of owning a French castle—as a value comparison to Bay Area real estate, and not because I was ever planning to buy a château. Here I’ll discuss the type of property we half-considered purchasing as our French second home—over and over again, all while knowing on some level that it would never work for us, in what amounted to the real estate-version of a distracting shiny object: the reno in a lovely setting.

To people from mostly expensive, developed, and Anglophone parts of the world—Britain, Australia, Canada, the U.S.— prices for real estate in much of France are so low they can seem a little silly. Take the sprawling stone farmhouse on a green Gascon hillside half-acre with Pyrenées views for the price of a Honda Accord. Sure, the house had not been updated since a Napoleon was in power, and several walls had dissolved into rubble. But it was a generous, sun-drenched piece of “la France profonde”—deep, true, profound France.

In addition, bargain-hunting is one my few true, time-tested hobbies; you’ll find me browsing the back-of-the-store racks first. So in my early-pandemic French real estate website wanderings, I usually stuck with the “lowest price” search option—where homes endlessly abounded in the five-figure range and presented tantalizing photo tours of various graceful French countrysides.

Then I realized that many properties looked vaguely familiar—because we’ve all seen this movie before.

not recommending it; not not recommending it

For decades now, the default dream involving a move to a picturesque part of continental Europe is to buy an interesting but partially ruined house in a beautiful, still-affordable region and then spend a year or two renovating it, hiring local contractors and artisans to do the skilled work, befriending them and their families along the way. Et voilà: you’re the proud owner of an incredible house and a settled, language-conversant member of the community, just as you’ve coincidentally made real estate prices skyrocket all around you thanks to your lovingly written internationally best-selling memoir of said home renovation. This may have only worked for Peter Mayle in Provence and Frances Mayes in Tuscany, but everyone has read—or heard of—at least one of those books. The moral of these stories especially appeals to workaholic societies and cultures: A smart buy and plenty of elbow grease will be rewarded with two-hour lunches on sun-dappled terraces ever after.

Given my tastes and temperament, I was far more intrigued that a very different sort of writer, David Sedaris, had also undertaken such a reno project—and in Normandy, clouded in a Northern European climate equivalent to my beloved Brittany. He’d moved to the edge of a small, non-famous village with his boyfriend, where the two of them spent many summers rehabbing a traditional house themselves—work he made sound as demanding, dusty, and exhausting as you’d assume it to be. This impressed me no end, much as decathlon people impress me, or neurosurgeon people impress me for doing a very hard thing I would never do.

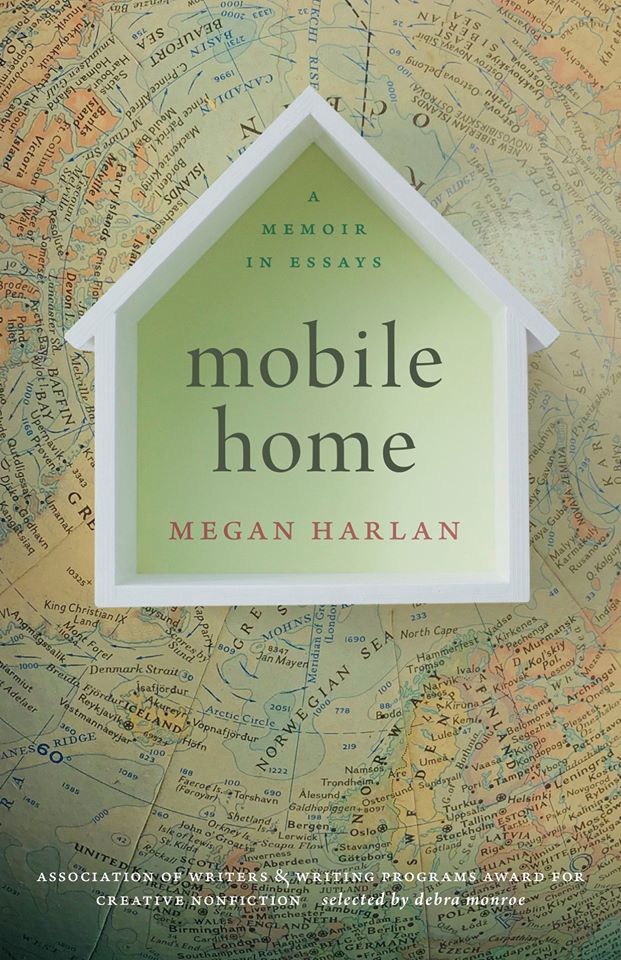

the cover this book deserves

Because throughout my bargain-priced house searches, a question always lurked inside me: Why would anyone want to do this—to actually live through this sort of renovation?

The obvious answer is because it’s the only affordable option, an ostensibly cheap enough buy to make owning the house possible at all. But since my partner and I are not structural engineers, architects, contractors, or particularly handy—never mind any of these pursuits conducted in French—how were these rubbly properties feasible options? They most likely offered us no bargain at all, since we’d have to pay professionals to restore one—for amounts whose scale I couldn’t begin to fathom. Or we’d ruin many a summer vacation by attempting the work ourselves, finally giving up at some point and trying to re-sell the place at a weird price. French real estate sites feature many of these sad, half-finished projects, the “partially restored” home. If their walls could talk, it’d be salty.

Some years back, my partner and I learned the limits of our (read: my) handiness as youngish parents and new homeowners. We’d bought a 1930s vintage house in great structural shape and pretty hideous cosmetic one; our plan was to spruce the place up ourselves. This made sense at the time: I truly love interior design and undertake occasional little painting or fabric projects; my partner amazes me by sometimes making useful things—wooden planters, garden shelves—with all those power tools in the garage. In addition, this was during peak HGTV years, where renovation shows presented do-it-yourself contracting work as a perfectly normal, even “fun” thing for amateurs to do. Couples who looked not unlike us and equally untrained in homebuilding skills were undertaking entire renovation projects while wearing fairly cute outfits, maintaining their composure, and making very little mess. Why couldn’t we?

So we decided to repaint our kitchen cabinets ourselves.

One sunny Saturday morning we cleared everything out of the cabinets. We unscrewed all the cabinet doors, brought them into the backyard, and my partner introduced me to two terrible new implements: a scraper and a hand-sander. I stared at them, wondering what they had to do with me. For some reason it was only then that I finally realized what we were planning on doing: Scraping and sanding paint off of dozens of cabinet doors; doing the same to the frames inside; then painting all of these surfaces in layer after smooth, seamless layer. The stark, vivid reality of the labor involved suddenly played before my eyes: It could take us months to do the job well, and a horrible couple of weeks to do it terribly. As otherwise employed people, this was a weekend effort; would it take us the rest of the year?

I may have silently begun crying; that’s the way partner remembers it. I do remember shaking my head “no” and repeating that single word like a mantra. My partner was confused; this was going to be fun! Nope; I was out. I would have paid anything to have someone else refinish those cabinets. We called our neighbors and begged for contractor recommendations; one outfit miraculously agreed to come on Monday. We hired them on the spot, and it all turned out fine—for the cost we should have ponied up to professionals to begin with. But I’ll never forget that moment of realization: I cannot handle this much sanding.

Now older, I’m slightly wiser for simply knowing my limits. I’m a writer—not a tiler, painter, or drywall installer.

And it’s lead to this insight: We want to live in a house in France, not renovate a house in France. As Gen X parents of a teenager, we did not want to fly our family to Charles de Gaulle from San Francisco, then train or drive to Brittany, only to spend all our waking hours doing contracting work, poorly.

the kitchen we did not have to renovate

As I’ll write more about in a future post, the Parisian writer and librarian from whom we bought our France house had spent years thoughtfully overseeing its renovation, hiring local artists and artisans to bring beautiful and creative flourishes to their work. I silently thank her and her crew of talented men every single day I’m in that house.

Finally, I named this piece as a little tribute to Anthony Bourdain. Like so many, I’ll always be a fan of his tetchy and hilarious voice, his brazenly curious, observant, and intuitive viewpoint. Below is his Brittany episode on No Reservations. It’s an especially lovely one, because he seems genuinely happy there, contented and at peace. (Warning: It’s behind a paywall.)

Someday we will order Brittany’s famous “tower of shellfish” in his honor. Salut.

[Header photo credit: © Yann Forget / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA.]