On the history and delights of the second home in town.

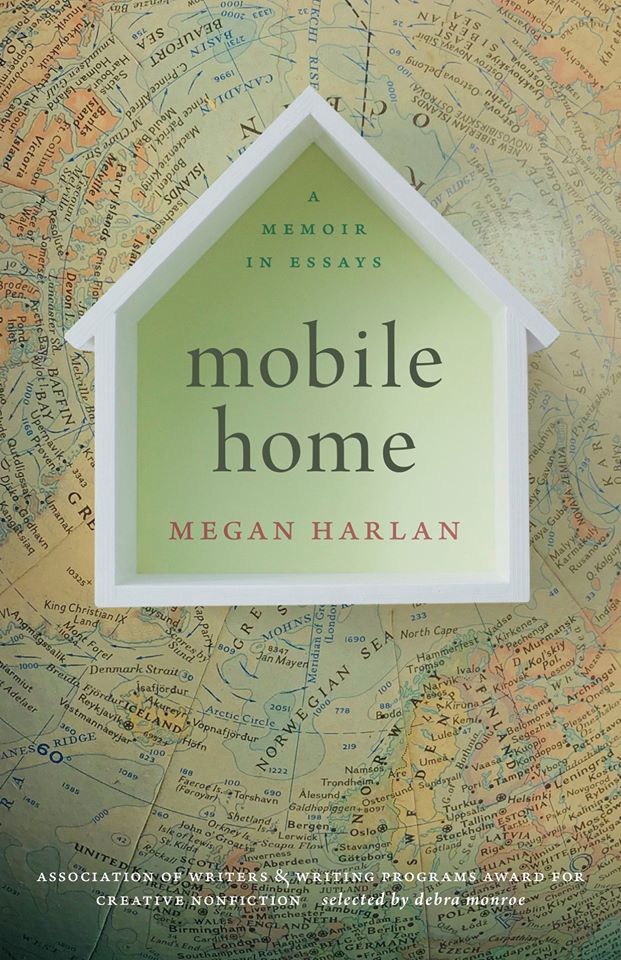

By Megan Harlan

I remember a conversation with my family during a holiday dinner when I was eight or nine years old: Who among us counted themselves a Country Mouse or a City Mouse? Nearly everyone decided they preferred “nature”: Country Mice they were. Only my maternal grandmother and I preferred the city. “We’ll pick the hayseeds out of your hair when you come to visit us,” she said to our family, smiling conspiratorially at me. I was delighted to be with my literary and arts-loving grandmother in our imaginary city pad, where I pictured us lounging on velvet chaises, snacks and drinks and books at the ready on pretty side tables, a view of twinkling streets out our windows: A bijou lap of urban elegance. My dreams have been consistent, at least.

While most second homes are located in “nature”—classic vacation getaways like a lake house or a ski cabin, since beaches, mountains, and waterways of all kinds are where most of us yearn to escape to—one exception stands, and it’s in French. When we say pied-à-terre, it’s the only instance where the second home is clearly in an urban place.

a Renaissance-era apartment building in Dinan, formerly the Hôtel de Beaumanoir

I’ve been hunting for the etymology of pied-à-terre, having always wondered about its odd literal meaning, translating verbatim as “foot to earth.” Merriam-Webster claims it derives from an older phrase, mettre pied-à-terre, one hailing from the French calvary—for whom it meant “to dismount a horse” (literally “to put foot to earth”). Soldiers after a day of travel would immediately hunt for temporary lodging in town—thus the connection to a part-time urban dwelling that’s survived as the term’s connotation today. Pied-à-terre may sound “fancy” to Anglophones, but I like how it’s grounded in bodily motion: You can imagine the thump of feet as someone lands on the ground, after swinging themselves off a saddle. Then off they head into city streets to take some rooms.

Frank O’Hara wrote, “I can’t even enjoy a blade of grass unless I know there’s a subway handy, or a record store or some other sign that people do not totally regret life.” (This from his great prose poem, “Meditations in an Emergency.”) Count O’Hara and me City Mice. I well understand the impulse to escape “people” and head for the hills when the going gets tough—or when you’ve simply had enough of humanity’s incessant high jinks. But when I need to “escape,” I prefer to hunt for more inspiring expressions of human life than whatever has been annoying, boring, or disappointing me in my day-to-day world. I like nature fine, but I’m fascinated by human genius and creativity. It’s the form of “nature” I most respond to.

better than a hike: browsing this bookstore in nearby Bécherel, a French “City of Books”

My days in California center almost entirely on my family and my work, otherwise known as just-what-life-is: trying to keep us and our pursuits on track. Yet I will speak for everyone when I say: It’s really, really good to get away sometimes. Our choice to have a pied-à-terre in a historical Breton town is to solidify this “getting away” into an experience more tangible and meaningful than a mere vacation: a place for my people and me “to get back to culture.”

The France House is our experiment in what a home can be beyond the plainly obvious, that building where we store our underwear, brush our teeth, pay the Netflix bill, and cook the nightly meal. Like all “vacation homes,” it’s freed from many of the regularly scheduled programs, responsibilities, and habits that take up so much space in our normal lives—even in a good way. But it’s also a home where we can step outside the front door and allow ourselves the time and mindset to make discoveries.

this lovely woman is my mom, marveling at an incredible lock on Dinan’s Rue du Jerzual

what happens in Dinan’s Saint-Sauveur basilica when the sun begins to set

Dinan proper only has about 11,000 people—but in medieval times it was a major player and political force, appearing on the oldest surviving map of Europe, thanks to its ancient castle (and a super-interesting one; more on this in a future piece). With castles came big churches and the dense walled settlements and commercial centers to serve them. In other words, Dinan was built so long ago its size was considered “city” at the time, and so, like many grand old European towns, it often features the ornate textures of a city, designed with urban density and flourish—even if its footprint looks modest. It all makes Dinan seem city enough to me for a pied-à-terre.

I lived in New York, that most indisputable city, some years ago, where pied-à-terres are a staple form of real estate. When I first heard the term there, I pictured the luxury hotel suite in Joe Jackson’s “Stepping Out” video, where similarly overdressed couples—wielding fur capes and strings of diamonds, probably hailing from Greenwich or similarly moneyed Connecticut—stayed in “the city” for occasional nights on the town involving Broadway shows, suit-filled cocktail bars, and many martinis. But soon I had a boss who kept a very tiny pied-à-terre in Lower Manhattan’s “Financial District,” really Chinatown, a dismal kitchenless studio where he slept four nights a week—joining his family over the weekend at their regular home on Long Island. Glamorous was not how he described it. But useful, yes: Its proximity to the office allowed him the success in his job that helped finance his own dream life in the suburbs.

What we’ve done is sort of the opposite: Our suburban life in California inspired us to create a pied-à-terre nowhere near it—a second home that allows us, on a regular basis, to discover and connect to worlds beyond our backyard.

a home along Dinan’s Rue du Jerzual