On finding a new part of the world to call home.

By Megan Harlan

Why, of all places, did we choose Dinan, a medieval town in northern Brittany, for our second home? It’s not exactly well-known, at least not to Americans. Even our most travel-loving and Francophile friends hadn’t heard of it. And we’d only ever spent a week there, during a trip to Brittany in 2019.

Among our reasons, it’s safe to say this wasn’t a case of being dazzled by novelty, or the home-buying version of marrying your first crush.

We all have our own senses of how big or small the world is—and how much of it is within our grasp to explore. Some people can’t imagine going as far as Nepal, or Sicily, or even two states over; they’ve got everything they need right where they are. For others, such travel seems perfectly natural, a gift of being alive. Myself, I cast a wide net.

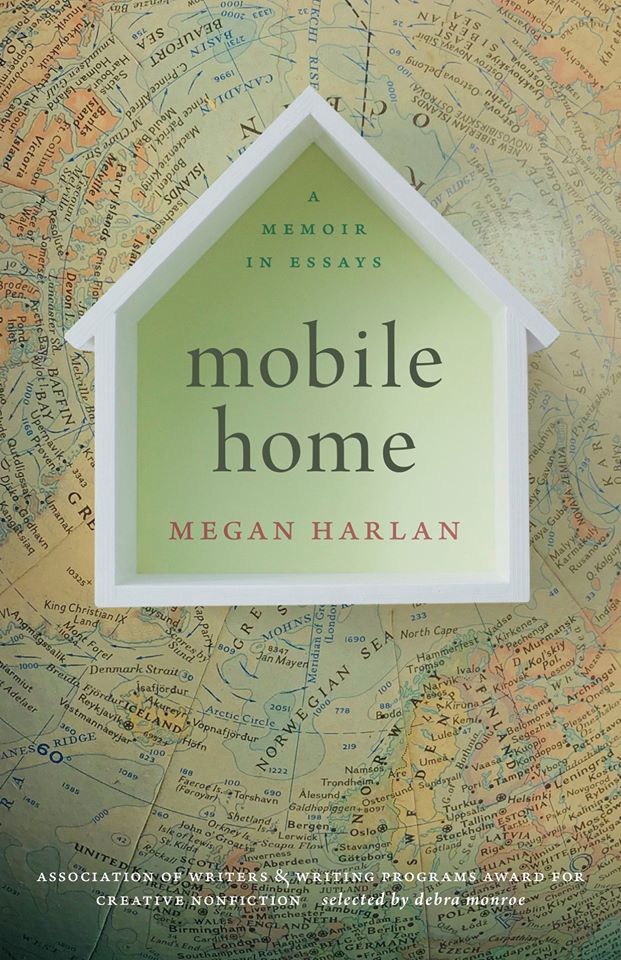

That’s largely because I was raised moving across the world, starting from a very young age. This widespread travel (five continents, more than 35 countries) began when my family moved abroad when I was seven and then kept moving—to places sometimes so far-flung that simply getting to them from the United States and back required a trip around the world. As an adult I continued this pattern of large-scale voyages, becoming a travel writer whose first assignment took me to the Sahara Desert. My most ambitious venture was a three-month backpacking excursion across Southeast Asia, including a month wandering across Bali, carrying little more than a sarong, a bathing suit, a journal, and a brick-thick copy of Lonely Planet’s Southeast Asia on a Shoestring. I was 24; it was bliss.

But the itch to add new places to that Countries Visited List has faded with time—and most definitively with the onset of parenthood. Since becoming a mother, I’ve yearned instead to burrow more deeply into a place that expresses what is in essence another side of myself, my partner, and our family than where we already live.

That primary home is California, a state I’ve always loved and still do—though not without seeing its flaws. My partner is a native; we’ve both lived there on-and-off our whole lives, and our son, for his entire one. Its big-boned landscape and gorgeous features are in the blood at this point, as are the climate and cuisines that will nearly spoil you to any other place, and such visceral imprints as San Francisco lighting up like a rainbow when the fog finally lifts, or Lake Tahoe’s crystalline morning smell of pine trees and glacial waters. But even at its best, California sits at an isolating distance from everywhere but other places sort of like it: Pacific Northwest, you are more like California than you probably want to admit; Mexico’s Pacific Coast, you’re often a sultry dead ringer for Santa Barbara. And these places aren’t even that close.

While California offers the scale of the natural world that just keeps going—few coastlines can compete for such grandiose beauty, few mountain ranges can transport you so absolutely into breathtaking views onto geological time—we wanted that sense of wonder and enormity but culturally, historically deep. Where you can see the marks left by a few different ancient civilizations. Where you are steeped in richly textured and time-layered built environments: Streets going back a thousand years—not a hundred, tops.

Rue du Jerzual, Dinan—a street dating to the 1100s

In short, my partner and I yearned for Old World; town over country; dense culture, not depopulated nature.

Years ago, we’d thought about a house in Ireland; we have plenty of Famine-fleeing ancestry between us (though sadly, not the dual-passport-granting Golden Ticket of an Irish-born grandparent). I’ve traveled there four times; I love the place. But Ireland really shines in its countryside; and for us, a country setting seemed too isolating as a part-time home.

In fact that decision really focused down our search, helping us to realize not only that we wanted to be in a town—but one with a train station. And we wanted those trains to connect—theoretically—to the rest of Europe.

Because of my partner’s job, we’d visited France when our son was in grade school (a truly dazzling stay in Lyon), and kept returning to Paris afterwards, having fallen in all-too-predictable love with the country. France; who knew? (I’d been to Paris in my 20s, but somehow it didn’t stick that time.) It wasn’t until August 2019 that we took our fateful trip to Brittany—and rambled across the northwestern French peninsula like it was a lost homeland. Brittany’s Celtic-infused culture, lush green landscapes, and serrated Atlantic coastlines resembled our favorite parts of the British Isles—brilliant mists of Ireland here, Somerset’s dappled glow there, Wales wafting in blue-greenly—while still being distinctively French. To write this as an equation: France x Ireland (or Scotland or Wales) = Brittany. This felt like the right mix for us.

a stretch of northern Brittany’s Pink Granite Coast (La Côte de Granit Rose) [Credit: Patrick Giraud, Creative Commons, link via image]

Filled with Brits, the region is easier on Anglophones than much of France, possesses an easy-going vibe often more akin to Dublin than Paris, and, for us, a magnetic combination of foreign and favorite elements: Anciently charming town centers, prehistoric megaliths studding forests and farmlands, dairy products fit for a Druid goddess, coasts named for emerald waters or pink granite, violet hydrangeas that billowed against countless slate walls. As for the weather: We live close to the San Francisco Bay and are acclimated just fine to wet skies. For the first time I could picture myself living in this place—and not some woman living an idealized French life, carrying a tiny dog in a designer bag I would never own.

Yes, in some ways we’d have obviously preferred Paris. But we didn’t have Paris townhouse-level money to spend. (We could, however, have bought a very nice Parisian parking space.) But Dinan is a four hour train ride from Paris—and the rest of Europe that theoretical train ride away.

In the next post I’ll go deeper into why we were drawn to Dinan itself. For now I’ll just add: We ultimately chose the town not for analytical factors like train stations and travel times to Paris—but because it felt right. In any big life decision, analytics are meaningless without intuition—and your readiness to trust it. Often, that is the trickiest part: Not overriding your own inner voice.

[All photos credited to the author unless otherwise indicated.]