On touching down again in the France House: a love story.

By Megan Harlan

We’re back—in Dinan for nearly a month. This is my first post about the France House written, well, on location. So this piece will be a little different: More impressionistic and in media res. I want to share the scene here as it’s unfolding, how it looks and feels and sounds on this particular morning. (If the love-fest becomes too much, just wait: In a future post I’ll get real about the 20-hour “commute” it takes to get us here—a rougher saga all around.)

Ah, morning—one that starts nine hours earlier than we’re used to. Our best trick for dealing with jet lag is to basically ignore it. We drink coffee like it’s water, take naps if we need to, and wake up for good when the sun finally gets us—in bedrooms with no curtains, to the sounds of Dinan:

my view first-thing: wood beams, church spire, antique foxed mirror reflecting white walls

bell-tower through our bedroom’s open skylight

I gaze at—and listen to—this bell-tower every morning. It features the characteristically tiered, rounded Breton style (one that looks faintly Scandinavian or West Asian to me) shared by dozens more across Dinan. Its bells keep time, of course, striking the hours, half-hours, and quarter-hours in chimes so low and soft they almost seem polite. They also ring music at unusual intervals (why 9:52am?), trilling occasional, lovely carillon songs. Their volume is about on par with the seagulls and pigeons and morning doves that flap around on nearby rooftops, cooing and calling. Together, the bells and bird-calls comprise the distinctively textured soundtrack of Dinan—and our house. Despite being one of those easily irritated “noise sensitive” people, I love this aural backdrop, these gentle sound weavings of nature and culture.

(Though it’s suddenly broken, as I write this, by the sharp clippity-cloppety of horse-hooves on cobble-stone—no doubt a quintessential sound in Dinan for hundreds of years, but a new one to us, since we’ve yet to see any horses riding around town. I dashed to the window to get this shot:)

(I love riding; must find out more about this…)

Time for coffee, because the truth is we’re all working: It’s not “vacation time” yet for us. My partner is still on-the-clock full-time via Zoom (meetings that connect him to various European countries, India, and—come evening—California). Our son is taking a virtual class via a program for high schoolers at UC Berkeley. And I’m on the hook for writing deadlines and research for a new project.

In short, we’re experiencing the France House like we actually live here. I have to keep reminding myself that we do in fact live here: this isn’t just a house we visit, stay in, or travel to. I’ve been to the France House five times now; my partner four; our son three. Yet I still marvel that this is our home. My sense of rootedness is slowly deepening, and it’s a new type of pleasure for me—a visceral, emotional, and psychological one, a unique, twining sense of both relaxation and growth. I’m discovering ways, new and old, to be myself here—which will always involve writing. Time to get to work.

the ceiling cut-out over the bed

The house, with its three tall floors, overall feels a bit like a tower. I leave the top floor, a converted attic with two bedrooms, an office area in the landing, and bathroom with separate water closet—all white-washed and topped with angled ceilings. It’s the first time I will descend the wooden spiral staircase to the ground floor, 34 steps down. Yes, that’s 17 steps per floor. I’ll run up and down this stairwell so often I call it “the workout room.”

the curve of the hand-carved banister and staircase

On my way down, I pass the salon with the pretty ceiling on the second floor (featured in the header). My office—which doubles as a guest bedroom, en suite thanks to the attached bathroom—is just next door.

But now I head to the ground floor (le rez-de-chaussée in French) with its thick exposed stone walls, high beamed ceilings—and the coffee maker. This level contains the kitchen, dining room, and a lounge area—otherwise known as the “forest room” thanks to a charming, exuberant wall mural commissioned by the previous owner. During rare heat waves, this floor happily keeps its cool.

dining area and part of the “forest room”

facing the kitchen from the dining area

I’ve doused my mug of very strong Illy coffee with local Normandy cream (at about a Euro a container, I’m addicted to this velvety stuff) and head back up a flight to the office to settle in. This room started out as “my” office, but we all three use it about equally, as we rotate around the house with our laptops—depending on who needs which Zoom background and/or stronger Wifi connection.

where I sometimes pretend to be Colette, who famously wrote everything on her daybed

It’s in this room, more than any other in the house, that something mysterious happens: I’m often filled with a sense of rightness; a clear, resounding feeling that I belong here; a sudden orientation to a deeper core of both this place and myself.

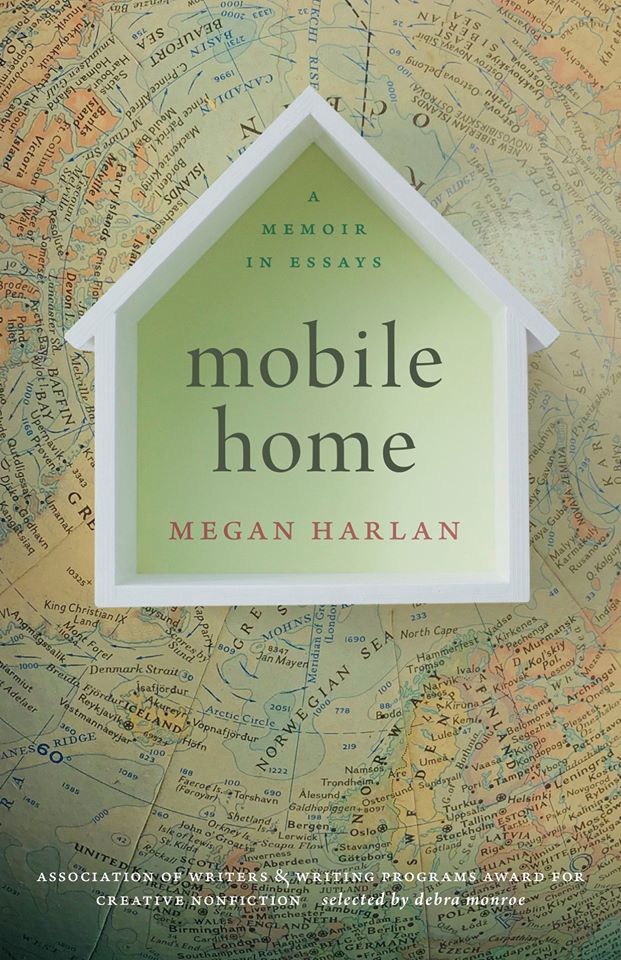

For my partner and me, buying this house was obviously a risk, and a rare thing we both desired that made no sense—unless you count our senses of beauty, truth, expansion, joy. We wanted to have these rooms of our own in France: A home to escape to, think, reconnect, and relax in; to marvel at the architectures and the roses, the cheeses and the breads; to absorb the French language into the system, as far as it will go. To give our son this background, this heritage. And for me, an essayist and poet: To bear down on the land of Montaigne—the creator, after all, of the essaie—and other literary loves like Voltaire, Colette, and Camus; Chateaubriand, Sand, and de Sevigné.

Even though my family is not playing “vacationers” quite yet, I’ve been relieved and sort of fascinated by how we well we fit here. We’re getting it done, all our many professional and educational tasks; we are work-driven Americans, after all. Yet we feel at home at this great distance from our primary one—while still aware of, alive to, and impressed by the differences all around us.

It’s an inspiring, irresistible combination to me, to all three of us. And it provides just about the perfect conditions for writing.